The world of specialty coffee is vast and varied, with each origin offering a unique story in every cup. Among the most prominent and distinct contributors are Indonesia and Colombia. While both countries consistently produce high-quality coffee, their individual journeys—shaped by unique cultivars, diverse geographies, intricate processing methods, and deeply ingrained cultural traditions—result in vastly different flavor profiles and coffee experiences. This article delves into a comprehensive comparison of these two coffee giants.

I. Cultivar & Geographic Factors

The foundational differences between Indonesian and Colombian coffee begin with the very plants they cultivate and the lands they inhabit.

A. Indonesian Coffee

Indonesia, an archipelago nation of over 17,500 islands, boasts an incredible diversity of microclimates and volcanic soils, making it a fertile ground for various coffee species.

Primary Cultivars:

While Robusta is widely grown and accounts for a significant portion of Indonesia’s overall coffee production, the specialty market focuses on Arabica. Common Arabica varieties include:

- Typica: One of the original coffee strains introduced to Indonesia.

- Hibrido de Timor (HDT) / Tim Tim: A natural cross between Arabica and Robusta, known for its disease resistance.

- Linie S (S-795, S-288, S-337): Selections from Typica and other varieties, often found in Java.

- Ateng, Gayo 1, Gayo 2: Local selections prevalent in Sumatra, particularly in the Gayo Highlands.

- USDA: A variety introduced by the United States Department of Agriculture.

Key Geographic Regions

Coffee is cultivated across numerous islands, each imparting distinct characteristics:

- Sumatra: Home to iconic names like Mandheling, Lintong, and Aceh (Gayo). The climate is tropical with high humidity and abundant rainfall, and the soil is often volcanic and mineral-rich, contributing to the coffee’s famed earthy notes.

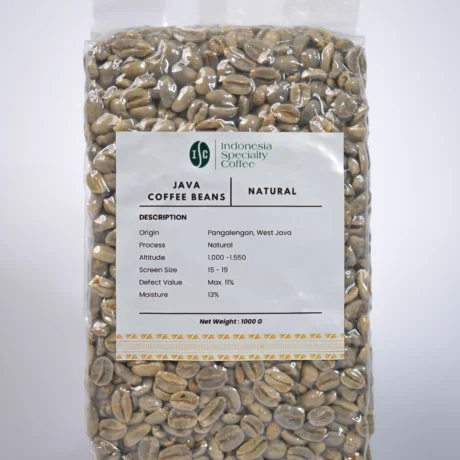

- Java: Historically significant for large colonial estates. Java coffee can be cleaner and more herbaceous, with some aged Java known for unique woody and spicy notes.

- Sulawesi (Toraja): Known for its high-altitude Arabica, offering full body, low acidity, and creamy texture with nutty and chocolatey aromas, sometimes hints of black pepper.

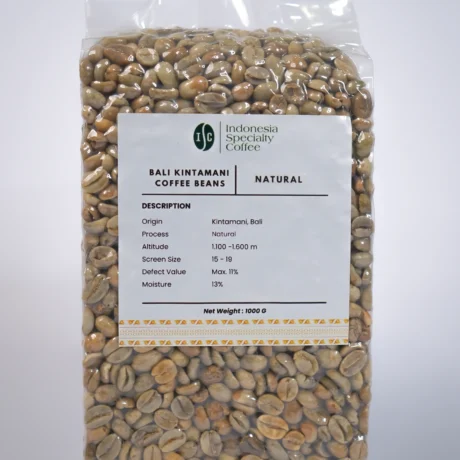

- Bali, Flores, Papua: Other islands producing specialty Arabica, often with unique fruity or floral nuances due to their specific terroir and often organic farming practices (e.g., Kintamani coffee from Bali).

Climate & Terroir Influence

Indonesia’s equatorial location ensures a tropical climate with consistent warmth and high humidity. The prevalence of volcanic activity throughout the archipelago provides incredibly fertile, mineral-rich soils. This combination, alongside often shaded cultivation, contributes to the coffee’s low acidity, heavy body, and distinctive earthy, spicy, and sometimes wild or herbal flavors.

B. Colombian Coffee

Colombia, situated in the Andean mountain range, benefits from an ideal combination of altitude, climate, and topography for growing high-quality Arabica.

Primary Cultivars

Colombia almost exclusively grows Arabica coffee. Key varieties include:

- Caturra: A natural dwarf mutation of Bourbon, known for its high yield and good cup quality, though susceptible to leaf rust.

- Castillo: Developed by Cenicafé (Colombia’s National Coffee Research Center), this hybrid is highly resistant to coffee leaf rust while maintaining excellent cup quality, and is now the most widely planted variety.

- Typica: An older, classic variety, valued for its bold and complex flavors, though with lower yields.

- Bourbon: Known for its sweetness, but less commonly cultivated in Colombia due to smaller bean size.

- Colombia F6 (Variedad Colombia): Another rust-resistant hybrid developed by Cenicafé.

- Tabi: A cross between Typica, Bourbon, and Timor Hybrid, also developed for disease resistance and good cup quality.

Key Geographic Regions

Colombia’s coffee is grown across numerous departments, primarily in the Andean region:

- Huila: Often praised for its bright acidity, floral notes, and fruity sweetness.

- Nariño: Known for vibrant acidity, complex flavors, and a clean finish, attributed to its very high altitudes.

- Antioquia: A large and historic coffee region, producing balanced and consistent cups.

- Eje Cafetero (Coffee Axis): Comprising Caldas, Risaralda, and Quindío, this region is the heartland of Colombian coffee culture, producing well-balanced coffees.

- Cauca & Tolima: Producing distinct profiles, often with notes of chocolate and nuts.

Climate & Terroir Influence

The Andean mountains provide high altitudes (typically 1,200 to 2,000 meters above sea level) and diverse microclimates. Consistent rainfall throughout the year, coupled with moderate temperatures and well-drained volcanic soils, allows for a prolonged ripening period, leading to the development of complex sugars and acids that contribute to Colombia’s characteristic clean, bright, and balanced cup.

II. Coffee Processing & Harvest

The methods used after the coffee cherries are picked significantly influence the final flavor. Indonesia and Colombia employ vastly different dominant techniques.

A. Indonesian Coffee

Predominant Processing Method: Giling Basah (Wet-Hulling)

This is the defining characteristic of much Indonesian coffee, particularly from Sumatra. It’s a semi-washed process unique to the region.

Process After harvesting, coffee cherries are de-pulped (outer skin removed) and undergo a brief fermentation (often overnight). They are then partially dried for a short period (2-3 days) until they reach a moisture content of 20-24% (much higher than typical dried parchment). At this stage, the parchment layer is removed (“wet-hulled”) by special machines while the beans are still soft and moist. The exposed, wet beans are then spread out to complete drying, often on patios, until they reach exportable moisture levels (around 12-13%).

Impact on Flavor & Appearance: Giling Basah contributes directly to the coffee’s distinctive earthy, savory, woody, and sometimes spicy notes, often described as having flavors of dark chocolate or tobacco. It also results in a heavy, syrupy body and low acidity. The process gives the green beans a characteristic dark green to bluish hue and a less uniform appearance due to the early removal of the protective parchment layer.

Other Processing Methods

While Giling Basah dominates, specialty producers are increasingly experimenting with fully washed, natural (dry-processed), and honey-processed methods, leading to a broader spectrum of flavor profiles, including cleaner, fruitier, or sweeter cups.

Harvest Method

Coffee cherries are almost exclusively hand-picked due to the mountainous terrain and the traditional smallholder farming model. This allows for the selective picking of only ripe cherries.

Harvest Period

Due to Indonesia’s vast geography and diverse microclimates, harvest periods can vary significantly by island and region, often occurring in two main waves or continuously throughout the year in some areas. For instance, Sumatra’s main harvest typically runs from September to June, while Java’s can be from July to September.

B. Colombian Coffee

Predominant Processing Method: Fully Washed (Wet Process)

This is the standard processing method across Colombia and is highly valued for producing clean and bright coffee.

Process: After harvest, ripe cherries are immediately de-pulped to remove the outer skin. The beans, still covered in a sticky mucilage layer, are then put into fermentation tanks with water. This fermentation typically lasts 12-24 hours, allowing enzymes to break down the mucilage. After fermentation, the beans are thoroughly washed with clean water to remove any remaining mucilage. Finally, the parchment-covered beans are dried, usually on patios or raised beds, until they reach a moisture content of 10-12%. Once dry, the brittle parchment is easily removed by hulling machines.

Impact on Flavor & Appearance: The fully washed process results in a remarkably clean, bright, and consistent cup profile. It accentuates the coffee’s natural acidity, sweetness, and distinct varietal characteristics, leading to notes of citrus, fruit, chocolate, caramel, and nuts. The green beans are typically uniform in color and appearance.

Harvest Method

Colombia’s challenging, often steep, terrain makes mechanical harvesting impossible. Therefore, manual picking is universal. Farmers practice “selective picking,” only choosing fully ripe red cherries, which often requires multiple passes through the trees over several weeks or months, ensuring optimal quality.

Harvest Period

Colombia is unique in often having two main harvests per year due to its proximity to the equator and consistent rainfall, allowing for fresh coffee to be available almost year-round. The “mitaca” (main harvest) and “traviesa” (mid-year harvest or fly crop) vary by region. For example, the main harvest in Huila runs from October to February, while in Antioquia it’s often September to December for the main crop.

III. Famous Varieties & Uniqueness

Both nations have specific varieties and overarching characteristics that set them apart on the global coffee stage.

A. Indonesian Coffee

Famous Varieties/Designations:

Kopi Luwak: Infamous for being processed by Asian palm civets. While highly expensive and unique in its origin story, ethical concerns surround caged production, and its actual cup quality is often debated by professionals, some calling it a novelty rather than a superior coffee.

Aged Sumatra/Java: Some Indonesian coffees, particularly from Java, are intentionally aged for several years in warehouses. This process mellows acidity and develops deep, complex flavors often described as earthy, woody, or spicy (cedar, cinnamon, clove).

Toraja Coffee: From Sulawesi, known for its bold character, low acidity, and notes of dark chocolate and fruit.

Gayo Coffee: From Aceh, known for its Complex Coffee Flavor with Hints of Vanilla, with Good Acidity & Medium to High Full-Body (Rich)

As an Indonesian coffee supplier, we have full coffee product lines from all regions in Indonesia. Check our products by clicking the button below:

Uniqueness Not Found Elsewhere:

- The Giling Basah Process: This semi-washed method is genuinely unique to Indonesia and profoundly shapes its cup profile, resulting in the heavy body, low acidity, and distinctive earthy, savory notes that are rarely found to the same degree in coffees from other origins.

- Quality Robusta: While often overlooked in specialty coffee, Indonesia produces some of the world’s best Fine Robusta, which, when well-processed, can exhibit notes of chocolate, nuts, and even fruit, adding unique dimensions to blends.

- Extreme Terroir Diversity: The sheer number of islands and varied volcanic landscapes within Indonesia creates an unparalleled range of microclimates and soil compositions, leading to an incredibly broad spectrum of flavors from different regions within the country.

- Historical Significance: Indonesia was instrumental in the global spread of coffee after its introduction from Yemen by the Dutch, with Java coffee historically being a major commodity.

B. Colombian Coffee

Famous Varieties/Designations:

- Juan Valdez: The iconic brand ambassador for Colombian coffee, symbolizing the hard work and dedication of Colombian coffee farmers globally.

- Colombian Supremo/Excelso: These are quality classifications rather than varietal names. Supremo refers to larger beans, and Excelso to slightly smaller ones, both representing high-quality washed Arabica.

- Regional Specificity: The emphasis in specialty Colombian coffee is often on the specific region of origin (e.g., Huila, Nariño) due to their distinct microclimates producing unique flavor profiles.

Uniqueness Not Found Elsewhere:

- Consistent High-Quality Washed Arabica: Colombia’s ability to consistently produce vast volumes of high-quality, clean, and balanced washed Arabica is unmatched on a global scale.

- National Federation of Coffee Growers (FNC): The FNC is a powerful and highly influential organization that plays a crucial role in supporting Colombian coffee farmers. It provides technical assistance, quality control, price stabilization, research (through Cenicafé), and global marketing for Colombian coffee, ensuring a consistent standard and protecting the livelihood of its smallholder farmers.

- Micro-lot Movement: Colombia has been a pioneer in the micro-lot movement, where small batches of exceptional coffee from individual farms are identified and marketed, highlighting the unique characteristics of specific plots of land and individual producers.

- Deep-Rooted “Cafetero” Culture: Coffee is more than just a commodity; it’s a way of life deeply ingrained in the social and economic fabric of Colombia, particularly in the coffee-growing regions.

IV. Unique Traditions of Drinking Coffee

Beyond cultivation and processing, the way coffee is consumed also tells a story about each nation’s culture.

A. Indonesian Coffee Traditions

- Kopi Tubruk: This is perhaps the most traditional way to drink coffee in Indonesia. Coarsely ground coffee is simply poured directly into a cup with hot water and often sugar, then stirred and left to settle. The result is a strong, thick, and sediment-rich cup. It embodies simplicity and a direct connection to the coffee.

- Kopi Joss (Yogyakarta): A truly unique experience, Kopi Joss involves dropping a glowing hot piece of charcoal into a cup of Kopi Tubruk. Locals claim it neutralizes acidity and adds a unique smoky flavor.

- Warung Kopi Culture: Local coffee stalls (“warung kopi”) are ubiquitous across Indonesia, serving as informal community hubs where people gather to socialize, discuss daily life, and enjoy simple, strong coffee, often with condensed milk.

- Condiments and Enhancements: Indonesian coffee is often enjoyed with generous amounts of sweet condensed milk (Kopi Susu), or sometimes spiced with ginger or other local flavors.

B. Colombian Coffee Traditions

- Tinto: The quintessential Colombian coffee. It’s a small, black, strong, and often pre-sweetened coffee, served frequently throughout the day. Tinto is a symbol of Colombian hospitality, offered to guests upon arrival in homes and at workplaces. It’s less about savoring complex notes and more about a warm, social ritual.

- Café con Leche: A simple coffee with milk, often enjoyed for breakfast, providing a milder, creamier alternative to tinto.

- Pasera: This refers to the act of taking a coffee break. In Colombia, coffee breaks are woven into the rhythm of the day, serving as opportunities for conversation, family discussions, or quick business chats.

- Emphasis on Freshness: Colombians often prioritize fresh coffee. Many households use small traditional filters (like a “media”) for brewing, and coffee is frequently purchased from local roasters or even direct from farmers.

V. Conclusion

Indonesian and Colombian coffees, while both stalwarts of the global coffee industry, stand as compelling examples of how terroir, processing, and cultural heritage profoundly shape a beverage. Indonesian coffee, with its signature Giling Basah process and diverse volcanic origins, offers a bold, earthy, and full-bodied experience, often with unique savory or spicy notes. Colombian coffee, on the other hand, embodies balance and cleanliness, consistently delivering bright, sweet, and well-rounded cups, largely thanks to its ideal growing conditions and meticulous washed processing.

Whether you seek the rugged, exotic depth of an Indonesian Sumatra or the comforting, consistent harmony of a Colombian Huila, both nations offer rich and rewarding coffee journeys, showcasing the incredible diversity and artistry inherent in every bean.

If you trying to buy Indonesian coffee, we are the right supplier choice for you. Contact us Now!